Police mourning their fallen colleagues, 2 June 2014, central Ivano-Frankivsk

This is the second of a two-part blog post. In the first part on the funeral of National Guard soldiers, formerly of Berkut, killed fighting for Ukraine in Donetsk region, I presented the mourning that took place in the city over at least three days since 29 May. Here I look more at the political controversies, as well as the questions for memory and memorial culture, that have emerged in light of these deaths and the burial.

The six men from the region killed in the helicopter, including the three buried in the Memorial Square, were members of the Berkut special police unit until it was disbanded after Yanukovych fled the country and the new government assumed power. These men had volunteered to transfer to the new National Guard, a unit that replaced the Internal Military, and is responsible to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which is also in charge of police.

Berkut officers were responsible for beating students and protesters on 1 December, which reignited the initial wave of Euromaidan protests and turned Kyiv’s Independence Square into the fortified tent city that was the heart of protests. Meanwhile, in eastern Ukraine and Crimea, after Yanukovych was deposed, in some places Berkut officers were greeted as heroes.

A Gryfon member and a member of the public

Troops from the Gryfon unit stand guard

When the Police and Security Service (SBU) HQ was being stormed in Ivano-Frankivsk on 18/19 February, Berkut officers -including the six men killed near Slovyansk in the “anti-terror operation” – were present in the city. Indeed, they were inside the building. First ordinary police officers were brought out of the police wing of the building on Lepkoho Street and were greeting with shouts of “the police are with the people”, so an almost forgiving and celebratory greeting.

Later Berkut officers emerged – including the six men being mourned from Ivano-Frankivsk region – were made to walk through what is termed “a corridor of shame”, a kind of “guard of shame”, basically. The Berkut officers were released from the building, disarmed and their body armour removed, while the crowd mostly booed them. However, what is only now being appreciated is that in abandoning their posts, the then-Berkut officers betrayed their oath and abandoned their duties. Had things turned out differently in Ukraine, this act could have faced serious consequences. At this point, then, these men refused to fire on fellow Ukrainians.

After the police HQ was taken over, the crowd moved towards the Security Service wing of the building. That wing was harder to take and better protected, with “activists”, many associated with Maidan Self-Defence and Right Sector – and notably its youth wing, Tryzub Bandery – soon preparing burning tyres and the Molotov cocktails which caused significant damage to the building. It was then partly looted, while both sides – SBU workers and “activists” – burned documents, with a smaller-scale storming of the prosecutor’s office taking place, too, with documents burned there. The events at the prosecutor’s office remain to this day shrouded in mystery.

So, Berkut officers, including the six men being mourned and the three men from the city buried in the Memorial Square alongside Roman Huryk, were in February perceived as some of the biggest enemies of the protesters on Maidan. Their unit was declared responsible for murders, hence the “corridor of shame” and, later, after the collapse of Yanukovych’s rule and the formation of new (para)military units, some members of Right Sector and Maidan Self-Defence refused to fight alongside ex-Berkut and Ministry of Internal Affairs fighters in the National Guard. Some of the tensions are still evident in this Vice News dispatch, for example. However, some units are reconciled and it is reported that a someone formerly from the Maidan units was among National Guard members in the helicopter, three of whom are now buried in Ivano-Frankivsk’s Memorial Square.

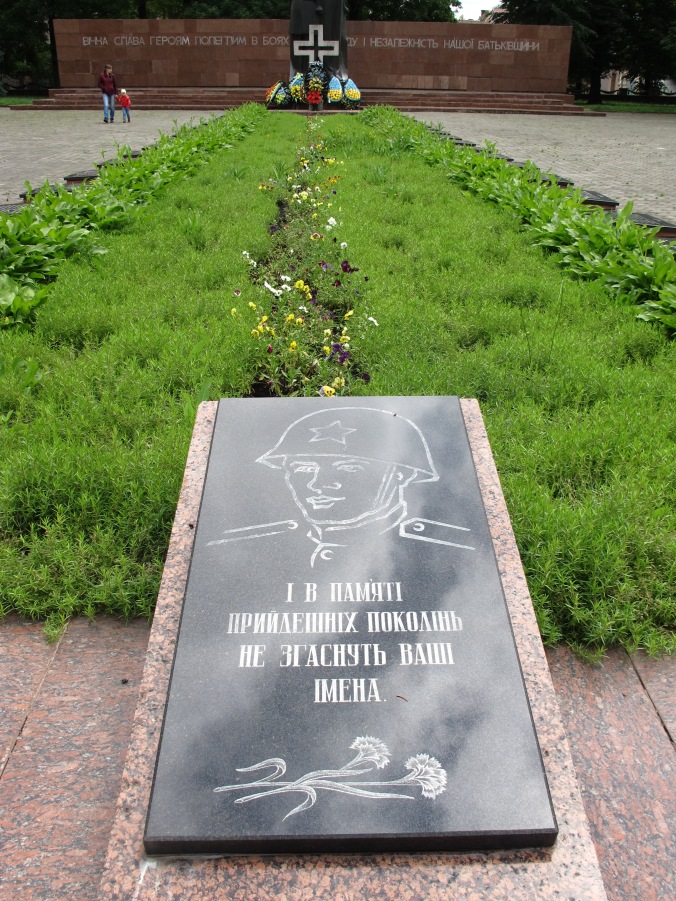

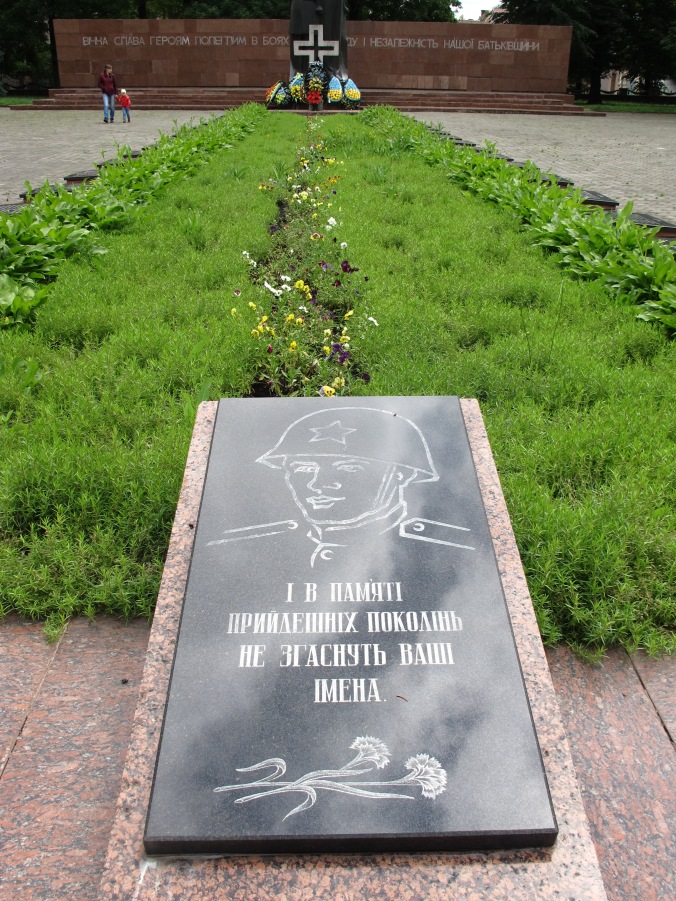

The Memorial Square is a palimpsest of memorial culture – forgotten Polish-Catholic graves slowly regaining some prominence after the cemetery was turned into a park by the communist authorities and the nearby church demolished to make way for the theatre. Since Ukraine became independent, and especially in the twenty-first century, some Polish graves have been restored, with a memorial to Polish military present, among the graves of Ukrainian cultural, academic and military figures. But the rest of the dead, ordinary people, are generally forgotten as the pantheon of Ukrainian heroes from cultural figures to freedom fighters grows.

The history of the Memorial Square becomes a microcosm of the complex history of the city and its residents. And this time again it will be a site revealing the difficult, ambiguous story of recent history, of Euromaidan and its aftermath, the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Killed in action defending Ukraine from a threat to its territorial integrity, the three men enter the pantheon of heroes here in Ivano-Frankivsk.

It would seem that given Ukraine’s current situation and the tragedy that has befallen the families of the men killed in action near Slovyansk, the term “heroes” would be enough to lend some decorum to this burial in Ivano-Frankivsk. Indeed, largely this has been observed, although a public spat has emerged which has called into question not so much the amnesty granted the men when they belonged to Berkut, but the behaviour of organisations like Maidan Self-Defence and Right Sector, who like to present themselves as living heroes, embodiments of the spirit of Maidan.

Three crosses for the fallen men, 2 June 2014.

The obvious tension that emerged with these men being buried alongside Roman Huryk, once deemed a victim of Berkut or associated snipers, was eased by the dead student’s mother who said she accepted the decision. However, her words reported in the press suggest a sense that the decision was taken over her head and she had little say, as the city council’s executive committee unanimously took the decision. Viktor Anushkevychus, the city’s mayor, spoke briefly on the matter, stressing the “symbolism” of Huryk “hero of the heavenly hundred” and “ex-Berkut heroes of Ukraine” being buried side-by-side, as it shows “that no one will be able to divide us”.

In this official statement, the totemic word “hero” is applied, seeking to heal all wounds and smooth history through what is in current conditions a sensible amnesty, casting aside partisan differences. Forgiveness had been issued to the Berkut men after walking the corridor of shame, they performed their penance, and on top of that they gave their lives for Ukraine, and only then earning their hero status.

However, close to the surface there still bubbles the ambivalence of relations between state and society, as Euromaidan and the deaths of the “Heavenly Hundred”, including that of local student Roman Huryk, have yet to be granted closure. Equally, whoever “we” are, who Anushkevychus states shall not be divided, is not clear. Is it the community of Frankivsk? Is it Ukraine – divided by Yanukovych’s government and now fighting united, with even former enemies now side-by-side? It’s not clear, especially given that Ukraine is now effectively engaged in a localised civil war. It is not proving easy to mobilise public enthusiasm, or indeed men to fight en masse, in what is proving to be a dangerously deadly fight in eastern Ukraine.

Ivano-Frankivsk’s newest street, running of Hetman Mazepa Street as part of a planned city centre bypass, is now named after Roman Huryk, the local student killed on the Maidan on February 2014.

During Euromaidan and the subsequent Crimea crisis, for people here, the enemy was clear: Yanukovych and the Party of Regions, Putin and his “little green men”. But now, heading eastwards to fight against fellow Ukrainians, even if they are supported by Chechens, Serbs or Russians, is less of an easy option than joining what were, at least until the final days of Yanukovych’s rule, largely a relatively safe form of mass protest during Euromaidan. Today, despite the threat to Ukraine, there is very little of the popular nationalism that seemed to flourish after the deaths on Maidan and the fall of Yanukovych. Instead, an atmosphere of fear and apprehension alongside a stubborn pursuit of everyday life prevails. And there is no cathartic compensation, for the community at least – obviously not for those who lost loved ones on Maidan – as there was when Roman Huryk was killed on Maidan, as by the time of his funeral, the rule of Yanukovych and his government was collapsing. Now, instead, the danger facing eastern Ukraine seems more real -regardless of the physical geographical distance – as local men fought and died there, leaving a trace of distant Donetsk in Frankivsk.

While some groups, particularly Maidan Self-Defence and, increasingly rarely now though, Right Sector, locally present themselves as the bearers of the legacy of Maidan, of heroism, it seems their claims lack social legitimacy. Now, as the threat grows more acute, it could become much more difficult to mobilise men to fight in eastern Ukraine, with volunteers serving in large numbers already now.

Any squabbles Maidan Self-Defence or Right Sector get engaged here in Frankivsk can seem petty when an acute threat faces Ukraine in the east and masses are dying on both sides, particularly with the Ukrainian authorities resorting to increasingly strong-arm tactics, including aerial bombing. (Ukrainian reports state 300 “terrorists” or “separatists” were killed just yesterday, 500 were injured, with two Ukrainian servicemen killed and 45 injured.) The harmony sought by burying the men as heroes, the unifying effect, has been disrupted on the local level by seemingly petty squabbles, as ghosts of past political differences emerge and the corpses of the dead are used for apparent points scoring.

Police HQ on 18/19 February 2014 after being stormed. The anti-Yanukovych graffiti was gone by the next day.

After the deaths of the ex-Berkut officers in the helicopter near Slovyansk, a local councillor, Mykola Kuchernyuk, stated that the deaths were partly a result of this looting of the security service and the failure of Self-Defence and Right Sector to return the bullet-proof vests and so on. (A big PR stunt emerged a few days ago, stressing that Self-Defence returned some vests, but the numbers don’t add up.) Indeed, after storming the the Security Service and Police HQ in February, the “activists” of Maidan Self-Defence and Right Sector looted some equipment, largely bullet-proof vests and shields, that were intended to be sent to Maidan in Kyiv or used in Frankivsk, if things got further out of hand.

Kuchernyuk can’t understand why the Self-Defence still need these vests, since ‘there has not been a single provocation noted by police against them’. In an escalation of the war of words that his first article provoked, Kuchernyuk has even called for an “anti-terror operation” in the city… to get rid of Self-Defence. He argues that the units have failed to disband or join the National Guard or Territorial Defence, as a parliamentary degree required them to do by 18 May. In the city, he believes, Self-Defence are terrorising the population and the authorities with their methods, including the APC outside the police HQ. Kuchernyuk also rejects the organisations’ claims to speak for the people of the city – since, as he rightly recognises, the people of the city largely want peace and quiet, rather than paramilitary organisations fighting over local positions of authority.

The reemergence of the spectre of recent history and the failure to lay to rest the complexities and controversies that saw the city divided and protesting in February against the state security apparatus, which is now afforded hero status, put Right Sector and Self-Defence in a difficult situation. People in the city and the local press remembered that it was these organisations that formed the Corridor of Shame and then looted the security service, taking away vital protection equipment. Of course, lacking the benefit of hindsight, the actions in February seemed justifiable in working towards bringing down Yanukovych’s rule and his security apparatus.

So, in a sense one aspect of the response from the Maidan “activist” core is understandable: don’t blame us, we were doing what we had to at the time. And their response that some politicians and councillors today, including Kuchernyuk, are seeking to exploit the helicopter tragedy for political gain today, seems reasonable. More questionable, perhaps, is the assertion that the “corridor of shame reflected the demands of the community”, as it is never clear in the conditions of mob democracy that emerged during the sharp end of protests here which elements of the community are represented in the actions of the most active elements.

Of course, the response to the accusations against Right Sector and Self-Defence have taken on an ad personam quality, with Kuchernyuk’s past membership of the Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (United) emphasised, since this Party sided with Yanukovych against Yushchenko around the time of the Orange Revolution presidential elections. This led to the councillor being labelled now “a potential Judas separatist” (see the caption accompanying the linked article’s picture). This same report, which neatly spans in its allusions to betrayal the entire cultural-historical spectrum relevant here in western Ukraine – from the crucifixion of Christ to the martyrdom of today’s Ukraine – also attempts, however, to falsify recent history.

What a building that hasn’t been subject to an arson attack looks like, apparently, according to frankivsk.net.

The report claims, ‘As everyone knows, really Right Sector and Self-Defence protected the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MBC) of Ukraine buildings from marauders. And it is only thanks to Right Sector that there were no arson attacks on the MBC in Ivano-Frankivsk.’ Maybe in Ukraine there is some technical definition of arson (підпал) that I’m not aware of and the term does not in fact cover throwing burning molotov cocktails through windows of a building with people inside. But I saw the building on fire that night. And maybe there is some definition of ‘marauders’ that I don’t understand, but the aftermath of the events of 18/19 February suggests a significant level of looting and damage, with repairs subsequently estimated at $1 million.

Now, just maybe, the young men and teenagers we saw filling up molotov cocktails were not part of Right Sector. But that seems unlikely, given the commands that were being issued that evening and the fact that numerous Tryzub members – incorporated into Right Sector – were out that evening.

It seems that the controversies emerging from Euromaidan and subsequent protests have a long way to run. And, rightly, in time they should be debated, but such squabbles appear unbecoming while the dead are waiting to be buried or have just been laid to rest.

Top: “Eternal glory to the heroes who fell for the freedom and independence of our fatherland.” Bottom: “And in the memory of generations to come your names will not be forgotten.”

Still, it is interesting to observe now are the local-level debates, confrontations and images that emerge, giving some insight into the way the memory and subsequent history of events is constructed. While battles rage in eastern Ukraine now, with civilians and combatants dying and suffering injuries, here in western Ukraine some apparently rather petty battles are taking place, battling for the future: the future right to write history and secure the strongest claims to the totemic term “hero”.

For now, though, aside from petty struggles seeking to usurp apply labels of good and bad, heroism and betrayal, the sensible approach to push forward for now a sense of amnesty and unity reveals the complex processes that await the historiography of Euromaidan and its aftermath. And these processes are evident in vernacular memory, which recognises often that circumstances change, individuals as members of organisations end up in unforeseeable situations that make them seem an enemy to some, heroes to others, then another change and perceptions are reversed.

In this way, vernacular or popular memory can seem to serve as a better archive of the ambiguity of historical events. However, over time it can submit to authoritative narratives that emerge which want a simplified history, black and white definitions of heroes or enemies, making the imagined nation or the political state, rather than ordinary people, the agents of historical and political change.

Mothers and children mourn in monumental form their fallen fathers and brothers.

The Red Army war memorial, Ivano-Frankivsk, 2 June 2014.

Meanwhile, whatever the grand narratives of relations between western Ukraine and the Red Army, ordinary people still come to mourn their lost loved ones a sites of memory around the city, including the Red Army memorial. No longer the premier site of memory in the city, it still has significance for families affected, as the Memorial Square now becomes the central site of mourning and heroism in the city.

And, sadly, these new sites of memory, mourning and heroism emerge because of further tragedies befalling families in this region in military action that, in turn, is causing tragedies for people in eastern Ukraine and elsewhere.